North Miami, Florida, USA, le 4 Juillet 2024

Au : Minister of Justice and Public Security

Me Carlos HERCULES

In his Offices

Subject: Information, request and proposal

Minister,

I apologize for having to disturb you from your many occupations. But, I am convinced that I must do it for the good of our country, the vitality of our justice and the protection of the young Haitian democracy, crushed at times under the boots of uncivil virtues that bend the existential impasse in which we found ourselves.

I am writing this letter to draw your attention to a fundamental issue related to both the morality of judicial institutions and the integrity of the act of judging, embedded in what the 2007 legislators call the certification of magistrates of the judicial order.

I address your honor in your capacity as Keeper of the Seals of the Republic, privileged witness of the serious hour that we are living and of the commitments that will be made to raise our country from the ground. I also address you, in your capacity as a jurist steeped in the great theories of Law and the practice of Law in its essentials.

I am writing to you on the eve of the elections scheduled to elect most of the councilors who will make up the fifth judiciary because I believe it is appropriate to remind you that there is a fourth judiciary that is leaving, leaving behind a heavy record of protests and a legal action before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights against the Haitian State for violation of the fundamental rights of judicial officials.

Minister,

The certification of the High Council of the Judiciary (CSPJ) is provided for by the law on the status of magistrates and the law creating the High Council of the Judiciary. This essential formality is intended to moralize the Haitian judiciary, at a time when justice seems to be losing its bearings. Moreover, the laws sewn together in 2007 have the virtue of getting the national justice system out of the impasse of infamy in which it seems to have been plunged for several decades. The installation of the council is above all at this price. The government of judges, supposed to be a champion of example, had to implement these two laws. And it had to do so in the urgency of its enthronement to breathe new life into the national judiciary, trapped in the Minautore that is systemic corruption. The implementation of these two texts with regard to certification required an implementing law, in accordance with the provisions of Article 70 of the law on the status of the judiciary. Despite the fact that this implementing law has never seen the light of day; the council, all courts combined, has already carried out several cohorts of certifications, which have knocked out onto the pavement nearly half of the magistrates who have been subjected to this sieve. However, if the first 3 courts used the memorandum of 20 November 2014 as a substitute for the certification procedure; the fourth court, for its part, declares that it is not aware of said memorandum, which is not recorded anywhere in the CSPJ archives. Clearly, the latest cohorts of certifications are carried out on the basis of a non-public procedure.

Beyond the debate leading to the conditions for achieving certification, It is wise to question the possible collision of non-certification and the acquired rights of non-certified magistrates. What effect can certification have on non-certified magistrates, given that the law, in its letter, does not pose this problem? The reality is that the governing body of the judiciary unceremoniously dismisses non-certified magistrates, with total indifference to their acquired rights. Beyond the question of acquired rights which seems to me to be of great importance, it is worth asking whether, in light of the major principles of law and in particular that establishing that the appointing authority is itself the revocation authority, the CSPJ can dismiss magistrates from the judicial institution even if they are not certified without a disciplinary decision having the force of final judgment.. The successive hitches observed at the level of what the CSPJ calls certification oblige clear consciences to go and glean in other laws to see if the process has not violated other rights of people, yet imprescriptible. It is in this sense that I never cease to question certification with regard to the acquired rights of non-certified magistrates. To this end, I assume that certification has no effect on the acquired rights of magistrates. This assumption is supported by two other secondary ones, namely that: “The CSPJ is not the body responsible for executing certification decisions and the implementation of certification decisions cannot be done without first taking into account the acquired rights of each party”. The question of the social benefits of magistrates becomes an imperative element of the analysis, given that the way in which they are driven out of the judicial system seems to pose the problem of respect for their rights acquired by their sole status as civil servants. This is why a careful look at the different laws and theories of law that clash in the context of decisions not to certify magistrates is necessary to enable us to untangle the tangle of work.

The judge with regard to the Haitian public service

Magistrates are responsible for applying the law. They fulfill a constitutional mission and belong to one of the powers that constitute the foundation of the Haitian State. Article 59 of the Constitution proclaims that: “Citizens delegate the exercise of sovereignty to three powers: the legislative power, the executive power and the judicial power”. The decree of August 22, 1995 relating to the judicial organization proclaims in its article 2 the functional independence of the judicial power: “The judicial power is independent of the other two powers of the State. This independence is guaranteed by the President of the Republic”. This judicial power, independent of the other two, is administered by the High Council of the Judiciary, which guarantees the career progression of magistrates and ensures the discipline of judges. Magistrates are civil servants with a special status. Article 6 of the law on the status of magistrates states that magistrates are installed in their functions upon taking the oath.

In short, the independence of magistrates is guaranteed by both the constitution and the law. As civil servants with a special status, they must take the customary oath before taking office. The constitution imposes the obligation of these formalities which constitute the starting point of the judge’s mandate. Article 2 of the decree of August 22, 1995 states that: “Members of the judiciary and ministerial officers are subject to the obligation to take an oath before taking office.” These provisions are corroborated by the provisions of Article 6 of the law on the status of the judiciary. With the exception of the justice of the peace and his deputies, the formality of taking the oath is the one that places the judge in his comfort, nicely called inamovibility. Judges are irremovable.

The Center for Textual and Lexical Resources defines irremovability as “the prerogative of certain magistrates and officials by virtue of which they cannot be moved, demoted, dismissed or suspended from their functions, without the implementation of protective procedures that are exorbitant to common disciplinary law.” In Haiti, judges of the courts of first instance, those of the courts of appeal and those of the court of cassation benefit from irremovability of judicial offices. Irremovability means that the appointing authorities no longer have any power, any possibility of revoking the mandate of judges except for reasons provided for by law. Article 117 of the decree of August 22, 1995 states unambiguously that “judges of the court of cassation, those of the courts of appeal and of the courts of first instance are irremovable. They may only be dismissed for legally pronounced forfeiture or suspended following an indictment. They may not be the subject of a new assignment, without their consent, even in the event of promotion. Their service may only be terminated during their term of office in the event of permanent physical or mental incapacity duly established. The same decree of 22 August 1995 proclaims in its articles 17 and 18 that the judge who, in criminal matters, is subject to physical constraint ordered by a judgment which has become res judicata, is deemed to have resigned; he is thus dismissed automatically if he has been sentenced to an afflictive and infamous penalty which has become res judicata. So, we are allowed to ask whether non-certification derogates from the principle of the irremovability of the magistrate’s mandate, as prescribed in the articles cited above. And if so, what is the legal framework that proclaims this? It is to these wise reflections that I would like to challenge you.

The judge is a civil servant recruited by competitive examination or by direct integration. He belongs to the civil service and is called to a career. In its article 236.2, the constitution proclaims the civil service as a career, that is to say a place where the recruited civil servant occupies permanent positions and where he acquires experience through most of the services offered by the administration. “The civil service is a career. No civil servant may be hired except by way of competitive examination or other conditions prescribed by the constitution and by law, nor be dismissed except for causes specifically determined by law, sic”. As civil servants of the public administration, judges may be called to exercise functions in the central administration of the State without losing their right to return to the workforce of the judiciary. As civil servants, judges have rights and duties.

The rights and duties of the civil servant/judge

The civil servant/judge is a public agent, appointed to carry out a set of related attributions common to the execution of a specific mission. He is vis-à-vis the judiciary in a statutory and regulatory situation. Thus, he must serve the State with dedication, dignity, loyalty and integrity. Article 18 of the code of ethics on the civil service states that the civil servant is the representative of the State and acts on its behalf by virtue of the powers conferred on him by law.

As a member of the judiciary, the judge derives his legitimacy from the law. And the law requires him to be independent, impartial, honest, dignified and loyal. He is the guardian of individual freedoms and holds enormous sovereign power in the sense that he judges in the name of the Republic. This is why he must pay attention to the actions to be taken for fear that he attacks the dignity of anyone or perverts the image of justice through acrobatics. Can the Governance Council of the Judiciary boast of never attacking the dignity of magistrates who are thrown into the trash in the name of a certain lack of moral integrity, circumscribed nowhere? How has it preserved the image of justice through its judgmental decisions?

The reality is that certification is carried out by an instruction committee supposedly composed of members appointed by the d two steering bodies of the judiciary. At the end of each process, this commission, after analyzing the evidence and/or proof, makes recommendations on a case-by-case basis. The council then intervenes to ratify or reject them. This decision is in itself a judgment similar to the orders of the interim relief chamber. However, if in interim relief, the judge can decide by default against a party; in matters of certification, there is an obligation to confront the magistrate concerned with the accusations made against him. Thus, the CSPJ is required to listen to judges facing serious or minor denunciations or accusations, if the commission fails in this duty; to assess the admissibility and credibility of the clues or evidence that have been brought to its attention. Not having done so, it is to deny magistrates the benefit of the rights that the law grants them. And among these rights, it is necessary to retain the right to be informed of proceedings opened against them and the right to defend themselves. There are also social benefits that are acquired rights, such as the irremovability of mandates and retirement for certain categories of magistrates.

Acquired rights of magistrates put to the test by non-certification

Judges, like all civil servants, have rights that their contractual situation guarantees them. These rights are called social benefits, which can be grouped under the label of social rights, apparently a right to integration and cooperation, according to Georges Gurvitch. The Council of Europe considers social rights as essential rights, indispensable to human beings in their quest for a dignified and autonomous life. Social rights are a set of rights encompassing the right to health, education, food, social security and protection at work. Is it in this sense that the philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon takes Law as the confluence where individualism and collectivism are realized? Labor law has the virtue of assuming the protection of workers, in particular by prohibiting them from being dismissed by a will not justified in fact and outside of a strict legal framework.

The issue of acquired rights always refers to a situation of conflict of law, in particular a conflict between an old law under the aegis of which legal situations were born and realized, and a new law giving rise to new ones. In the field of labor law, the old law that governs contracts remains in place until its full realization. Rights refer to the recognition of a right that has been established and has already produced its effects. This is the case of the mandate deemed irremovable. This irremovability is even a constitutional principle. This is also the case of the right to retirement for a certain number of magistrates, a right provided for by article 51 of the law on the status of the judiciary which states that: “… Judges are allowed to assert their right to retirement at the age of (55) years, after having provided twenty-five (25) years of service”.

What is the effect of non-certification on these two rights?

Certification is governed by the provisions of Articles 69 and 70 of the Law on the Status of the Judiciary and those of Article 41 of the Law establishing the CSPJ. These twin provisions state that judges of courts and tribunals hold office until the position is filled in accordance with the Constitution and they have been certified as to their competence and moral integrity.

The clarity of these provisions leaves no room for procrastination. Judges of the courts and courts of appeal hold office for the entire duration of their term. However, when it expires, no renewal of their term will be possible for them without having been previously certified by the CSPJ. The text, in its context, is addressed to magistrates already in office at the time of the CSPJ’s enthronement. This is attested to by the provisions of Article 15 on the status of the judiciary: “When his term expires, the judge of the court of appeal or the court of first instance interested in being retained in the same functions may request a new appointment. This appointment is not automatic. To be eligible for it and have his name entered by a departmental assembly on a list to be submitted to the President of the Republic, obtaining a favorable opinion from the High Council of the Judiciary is necessary.” This favorable opinion is the certification provided for in the law.

For new appointments made under the aegis of the CSPJ, a favorable opinion in advance is essential. For all renewals of mandates, this opinion remains essential; because certification is a process that occurs throughout the magistrate’s career.

In the name of fairness, the certification commission cannot only investigate any magistrate. The CSPJ, composed of people supposed to have mastered the general principles of law, must not pass judgment on a report made only against him. It must be careful not to do anything that could jeopardize the rights of the defense and the adversarial principle. By these cavalier decisions, does the steering body of the judicial power intend to overturn the sacred principles that, until now, guide all procedures in matters of denunciation and accusation? The abandonment of the principle of fairness in the certification process constitutes a serious violation of human rights and the decisions that follow are a complete failure of impartiality.

Minister,

Public authorities are established to fulfill a mission and solve problems. They cannot create them. This is why the constitution invests the executive power through the President of the Republic to ensure the smooth running of institutions. I would therefore be grateful if you would bring this matter before the Council of Ministers for a State decision on this issue. Furthermore, I would ask you to propose to the Government of the Republic to create a commission to inquire about information on:

The procedural rules governing the latest certifications and their publicity; The conduct of these procedures denounced by more than one as being incriminating for having been carried out without their knowledge; Respect for the rights of magistrates highlighted by the certifications carried out by the fourth judiciary; The conformity of their suspension by the CSPJ, which thereby became the body responsible for implementing decisions of non-certification, among others. I thank you for the favourable reception given to the subject of this letter and remain convinced that, through your action, our generation will for once be at the rendezvous of trust and hope.

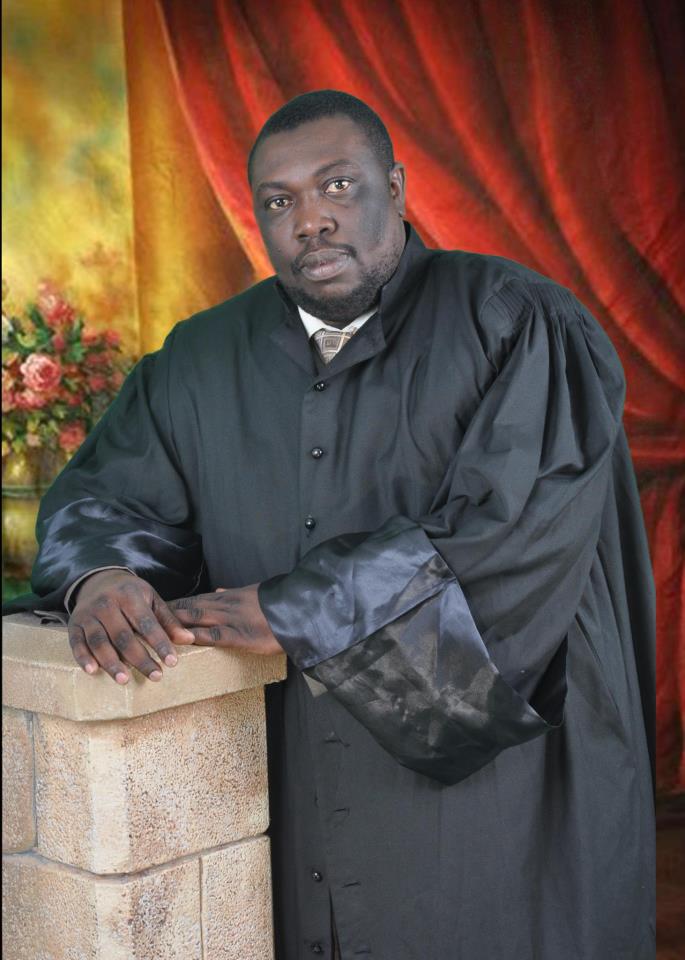

Jean Frédérick BENECHELawyer

Professor of Law

Specialist in Haitian Law

Researcher in African History and Culture

Master 2 training in Law and Safety of Activities

Maritime and Oceanic, University of Nantes, France

Former Judge at the Hinche Court of Appeal

Similar articles